About Iceland

Let us quench your thirst for knowledge about Iceland, whether it be geography, historical trivia or geological information.

Browse our impressive catalogue of information about Iceland and you will soon find out that your subject of interest is just one click away.

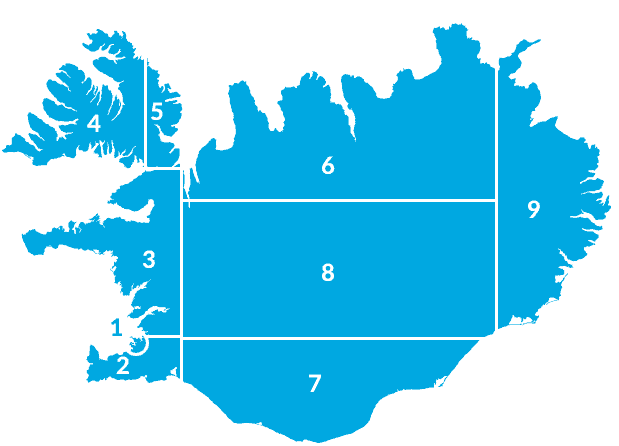

- 1. Reykjavík AreaReykjavík is the capital of Iceland, surrounded by suburbs and fascinating places.

- 2. ReykjanesReykjanes peninsula is full of geothermal wonders and also the home of Keflavík Airport.

- 3. West IcelandOne of the most famous attraction in the West is Snæfellsjökull glacier.

- 4. WestfjordsAn isolated part of Iceland, with a natural beauty beyond compare.

- 5. StrandirIf you’re looking for desolated wilderness and solitude, Strandir is the place for you.

- 6. North IcelandHome of Dettifoss waterfall, the most powerful waterfall in Europe.

- 7. South IcelandIceland’s most visited region, with plenty of waterfalls, black sand beaches and glaciers.

- 8. Highlands and interiorThe uninhabited region of Iceland, with amazing landscapes that are hard to find anywhere else.

- 9. East IcelandThe eastern part of Iceland is the home of the reindeers and Iceland’s biggest forest.

- Where to GO?

- WHAT TO SEE?

- All Attractions

- Churches

- Farms

- Film locations

- Fjords

- Geysirs and Hot Springs

- Glaciers

- Historical Sites

- Islands

- Lakes

- Mountains

- Museums

- Place of Interest

- Plains

- Rivers

- Towns

- Volcanos & Lava Fields

- Waterfalls

- What to do?

- All Activities

- Angling

- Deep Sea Fishing

- Golf

- Hiking

- Horseriding

- Hunting

- Icelandic Forests

- Lakefishing

- Murders

- Restaurant

- Saga Trail

- Salmon

- Swimming Pools

- Tours

- Travel Planning

- Trout

- Wintersport

- WHERE TO STAY ?

- All Accommodation

- Camping

- Cottages

- Farm Holidays

- Guesthouses

- Hostels

- Hotels

- Mountain Huts

Travel Guide

We’ve compiled a comprehensive list of places of interest in Iceland, whether it be churches, glaciers, islands or waterfalls.

We’ve also gleaned information about accommodation options all over the country, so you don’t have to. Simply select your area and start browsing.

Bus Schedules

Travel Iceland by bus and book your transport right here with us. You can book a one way ticket to almost anywhere in Iceland.

You can also plan your bus travel from A to Z and add numerous bus rides to your cart. Plan away!

Travel Market

Iceland has so many great options for any type of recreational activities. Our recreation guide will help you find great information on your favourite hobby or interest while visiting our beautiful country.

- 1. Reykjavík AreaReykjavík is the capital of Iceland, surrounded by suburbs and fascinating places.

- 2. ReykjanesReykjanes peninsula is full of geothermal wonders and also the home of Keflavík Airport.

- 3. West IcelandOne of the most famous attraction in the West is Snæfellsjökull glacier.

- 4. WestfjordsAn isolated part of Iceland, with a natural beauty beyond compare.

- 5. StrandirIf you’re looking for desolated wilderness and solitude, Strandir is the place for you.

- 6. North IcelandHome of Dettifoss waterfall, the most powerful waterfall in Europe.

- 7. South IcelandIceland’s most visited region, with plenty of waterfalls, black sand beaches and glaciers.

- 8. Highlands and interiorThe uninhabited region of Iceland, with amazing landscapes that are hard to find anywhere else.

- 9. East IcelandThe eastern part of Iceland is the home of the reindeers and Iceland’s biggest forest.

The Nine Wonders of Iceland

We split Iceland into nine different regions to make your search for information easier. Simply click on the region you want to explore and read about towns, attractions, hiking, accommodation and more.