GLAUMBAER SKAGAFJORDUR FOLK MUSEUM

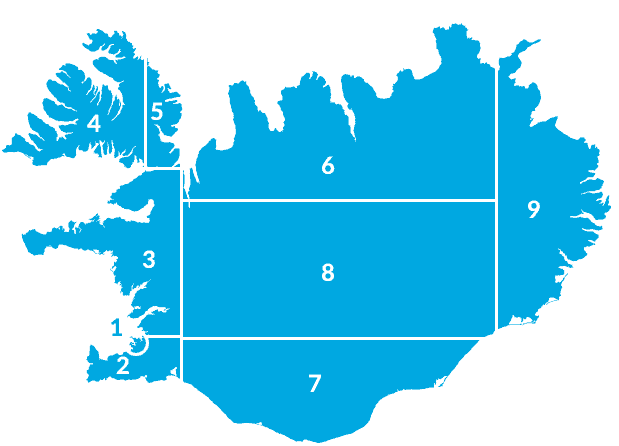

Region: North IcelandCoordinates: 65.6796756° N 19.5685996° W

The buildings of the farm group date from different periods of the 19th century and all were built in the turf construction style, which was  universal in rural Iceland until about the turn of the 19th century. Then it was gradually replaced by reinforced concrete, which is typical of most contemporary Icelandic construction. The Nordic ancestors of the Icelanders had built for the most part of wood. Extensive turf construction evolved in Iceland owing to acute shortage of large trees. Hence, the buildings at Glaumbaer are the thin shells of wood, all imported, separated from each other and insulated by thick walls of turf, and roofed with a thick layer of sod. The Icelandic grass grows very thickly making this turf and sod strong intertextures of roots and soil.

universal in rural Iceland until about the turn of the 19th century. Then it was gradually replaced by reinforced concrete, which is typical of most contemporary Icelandic construction. The Nordic ancestors of the Icelanders had built for the most part of wood. Extensive turf construction evolved in Iceland owing to acute shortage of large trees. Hence, the buildings at Glaumbaer are the thin shells of wood, all imported, separated from each other and insulated by thick walls of turf, and roofed with a thick layer of sod. The Icelandic grass grows very thickly making this turf and sod strong intertextures of roots and soil.

Such buildings in areas of moderate precipitation can last a century. The roof’s slope must be sloped at the right angle. If it is too steep, the sods crack during dry spells and the grass drains too quickly and withers and water will get through. The same happens if the roofs are too flat and the sods get saturated with water. It is too difficult to erect large structures of turf and sod. Therefore the Icelandic farm was a complex of small, separate buildings. The most used of those were united by a central corridor, but tool and storehouses could only be accessed from outside. The corridor at Glaumbaer is about 69 feet (21m) long and provides access to 9 of the 13 houses of the farm. Two intermediate doors along the corridor in addition to the front door kept cold from penetrating the living quarters.

See further information on the individual houses of Glaumbaer in the brochure of the Museum upon arrival there.

Glaumbaer’s chief renown lies in the actions and influence its inhabitants exerted both upon Iceland and the world at large. Their exploits ranged from being among the first settlers in North America and Greenland and to give birth to the first European on North American soil. They were heroic and influential people and were featured prominently in the ancient Icelandic sagas.

The first known inhabitants of Glaumbaer lived there in the 11th century. They are mentioned in the Saga of the Greenlanders and the Saga of Eirikur the Red, which tell of the explorers Leifur Eriksson and his brother Thorsteinn, sons of Eirikur the Red, of Thorsteinn’s wife Gudridur Thorbjarnardottir, her second husband Thorfinnur karlsefni and their son, Snorri. Gudridur Thorbjarnardottir is mentioned both in the Saga of the Greenlanders and in the Saga of Erik the Red. Gudridur, a granddaughter of an Irish freedman, was born in the 10th century in Snaefellsnes in western Iceland. She emigrated to the Icelandic settlement in Greenland founded by Erik the Red, and married his son Thorsteinn, who soon died. The young widow then married Thorfinnur karlsefni, a merchant and a farmer from Stadur in Reynines (now Reynistadur), Skagafiord District.

The first known inhabitants of Glaumbaer lived there in the 11th century. They are mentioned in the Saga of the Greenlanders and the Saga of Eirikur the Red, which tell of the explorers Leifur Eriksson and his brother Thorsteinn, sons of Eirikur the Red, of Thorsteinn’s wife Gudridur Thorbjarnardottir, her second husband Thorfinnur karlsefni and their son, Snorri. Gudridur Thorbjarnardottir is mentioned both in the Saga of the Greenlanders and in the Saga of Erik the Red. Gudridur, a granddaughter of an Irish freedman, was born in the 10th century in Snaefellsnes in western Iceland. She emigrated to the Icelandic settlement in Greenland founded by Erik the Red, and married his son Thorsteinn, who soon died. The young widow then married Thorfinnur karlsefni, a merchant and a farmer from Stadur in Reynines (now Reynistadur), Skagafiord District.

Gudridur and Thorfinnur explored Vinland, already discovered by Leifur Eriksson, Gudridur ’s former brother-in-law and later second husband. They spent the winter there, and planned to settle permanently. Their son, Snorri, was born in the New World. Due to conflicts with the Indians, they did not stay there long, and returned to Iceland. Initially they lived at Thorfinnur’s old home at Reynines, but then purchased the estate of Glaumbaer, probably shortly after 1010, and settled there.

After Thorfinnur’s day, Snorri took over the estate, and Gudridur decided to make a pilgrimage to the Pope in Rome, to be absolved of her sins. For a save return, she vowed to build a church to the glory of god. Snorri had a church built in his mother’s absence. Upon her return, she was saw the first known to have stood at Glaumbaer. On her return Gudridur became an anchoress, and lived in solitary worship thereafter.

Gudridur was without doubt one of the most widely travelled women of her time. She crossed Europe twice on foot, and made eight ocean journeys. She was a participant in Nordic exploration of new lands, lived through the change from heathenism to Christianity, and handled her role well. The symbolic depiction of Gudridur on this page is a photograph of a cast of a sculpture by Asmundur Sveinsson, dating from 1939, placed in front of the church at Glaumbaer.

AS HOUSE

The As house was built during the period 1883-86 at As in Hegranes and moved to Glaumbaer in 1991. It represents the architecture, which took over after the era of the sod houses. It was built to house a school of the domestic sciences, which was not to be. When its last inhabitant moved out in 1977, four generations of the same family had lived there. The married couple Sigurlaug Gunnarsdottir (1828-1905) and Olafur Sigurdsson (1822-1908), who built the house, were progressive people and supporters of youth education. They often organized courses for boys and girls in their home. During the period 1870-1900 many of the agricultural reforms in the area can be traced to As. Sigurlaug was a keen needle-worker and sowed the first women’s national costume of the present kind. She established the first women’s society of the country in 1869 and was in charge of the first School for Women in the district, founded at As in 1977.

At As, many novelties were introduced. Some of them were imported and others were improvements of old procedures or new inventions. The first pedalled sowing machine was introduced at As in 1870, the first knitting machine in 1874, the first stove shortly thereafter and the first spinning jenny in 1882. One of the sons invented pliers to cut the teeth of the wool-card, which saved uncounted days of work. At As was a windmill to grind grain and a pedalled grindstone to sharpen scythes and other edge-tools. At As, people got all kinds of instructions and progressive advice, which led to rationalization.

GILSSTOFA

The prototype of Gilsstofa was a wooden sitting-room from the middle of the 19th century. Such rooms were sometimes added to the sod farms and were predecessors of the wooden houses built shortly before and around the turn of the 19th century. This room was moved four times between farms during the period 1861-1891. Every time it was moved its purpose and form changed somewhat and new wooden boards were added.

Carpenter Olafur Briem of farm Grund in Eyjafiord built this room at farm Espiholl in 1849 for his brother Eggert. In 1861 Eggert became the district magistrate of Skagafiord and had the room moved to his new home, Hjaltastadir. In 1872 it was moved to Reynistadur, where it stood until 1884. When Johannes Olafsson at farm Gil became magistrate, the room was moved there. In 1891 it was moved to Saudarkrokur, where it stood until 1985 and served as a shop and a dwelling. Eventually it was reconstructed at Glaumbaer 1996-97, where it serves as the office of the museums of the Skagafiord District.

Such buildings in areas of moderate precipitation can last a century. The roof’s slope must be sloped at the right angle. If it is too steep, the sods crack during dry spells and the grass drains too quickly and withers and water will get through. The same happens if the roofs are too flat and the sods get saturated with water. It is too difficult to erect large structures of turf and sod. Therefore the Icelandic farm was a complex of small, separate buildings. The most used of those were united by a central corridor, but tool and storehouses could only be accessed from outside. The corridor at Glaumbaer is about 69 feet (21m) long and provides access to 9 of the 13 houses of the farm. Two intermediate doors along the corridor in addition to the front door kept cold from penetrating the living quarters.

See further information on the individual houses of Glaumbaer in the brochure of the Museum upon arrival there.

Glaumbaer in Icelandic

WHAT TO SEE?

Nearby GLAUMBAER SKAGAFJORDUR FOLK MUSEUM

WHAT TO DO?

Nearby GLAUMBAER SKAGAFJORDUR FOLK MUSEUM

WHERE TO STAY?

Nearby GLAUMBAER SKAGAFJORDUR FOLK MUSEUM

universal in rural Iceland until about the turn of the 19th century. Then it was gradually replaced by reinforced concrete, which is typical of most contemporary Icelandic construction. The Nordic ancestors of the Icelanders had built for the most part of wood. Extensive turf construction evolved in Iceland owing to acute shortage of large trees. Hence, the buildings at Glaumbaer are the thin shells of wood, all imported, separated from each other and insulated by thick walls of turf, and roofed with a thick layer of sod. The Icelandic grass grows very thickly making this turf and sod strong intertextures of roots and soil.

universal in rural Iceland until about the turn of the 19th century. Then it was gradually replaced by reinforced concrete, which is typical of most contemporary Icelandic construction. The Nordic ancestors of the Icelanders had built for the most part of wood. Extensive turf construction evolved in Iceland owing to acute shortage of large trees. Hence, the buildings at Glaumbaer are the thin shells of wood, all imported, separated from each other and insulated by thick walls of turf, and roofed with a thick layer of sod. The Icelandic grass grows very thickly making this turf and sod strong intertextures of roots and soil. The first known inhabitants of Glaumbaer lived there in the 11th century. They are mentioned in the Saga of the Greenlanders and the Saga of Eirikur the Red, which tell of the explorers Leifur Eriksson and his brother Thorsteinn, sons of Eirikur the Red, of Thorsteinn’s wife Gudridur Thorbjarnardottir, her second husband Thorfinnur karlsefni and their son, Snorri. Gudridur Thorbjarnardottir is mentioned both in the Saga of the Greenlanders and in the Saga of Erik the Red. Gudridur, a granddaughter of an Irish freedman, was born in the 10th century in Snaefellsnes in western Iceland. She emigrated to the Icelandic settlement in Greenland founded by Erik the Red, and married his son Thorsteinn, who soon died. The young widow then married Thorfinnur karlsefni, a merchant and a farmer from Stadur in Reynines (now Reynistadur), Skagafiord District.

The first known inhabitants of Glaumbaer lived there in the 11th century. They are mentioned in the Saga of the Greenlanders and the Saga of Eirikur the Red, which tell of the explorers Leifur Eriksson and his brother Thorsteinn, sons of Eirikur the Red, of Thorsteinn’s wife Gudridur Thorbjarnardottir, her second husband Thorfinnur karlsefni and their son, Snorri. Gudridur Thorbjarnardottir is mentioned both in the Saga of the Greenlanders and in the Saga of Erik the Red. Gudridur, a granddaughter of an Irish freedman, was born in the 10th century in Snaefellsnes in western Iceland. She emigrated to the Icelandic settlement in Greenland founded by Erik the Red, and married his son Thorsteinn, who soon died. The young widow then married Thorfinnur karlsefni, a merchant and a farmer from Stadur in Reynines (now Reynistadur), Skagafiord District.