Witchcraft and Sorcery, Iceland

The witch hunt in Europe started around the year 1480 and continued to the turn of the 17th century. The Icelanders were influenced by the Danes and the Germans during the period, but did not react until the persecutions were dwindling around the middle of the 17th century. It took on a different face here, as the witches and scorcerers were condemned for using magical characters and runes to cause harm.

The devil did not have much to do with Icelandic scorcery, and neither did black magic nor torture. Much fewer witches were burnt at the stake than scorcerers.

Dwindling in Europe

Around 1660, the witch hunt was dwindling in Europe. The year 1654 is considered the beginning of the Icelandic persecution with three people being burnt at the stake on cove Trekyllisvik in the Strandir District. The last burning took place on the alluvial plain Arngerdareyri on bay Isafjardardjup in the Northwest in 1683. Possibly the first man to be burnt was Jon Rognvaldsson in valley Svarfadardalur in North Iceland in 1625.

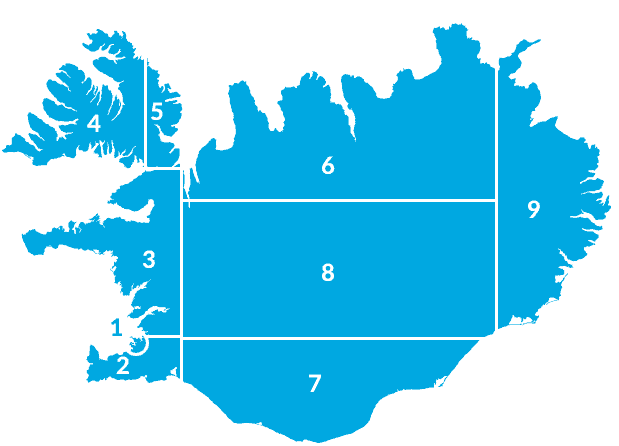

In addition to the twenty burnings, five are so vaguely documented, that historians are not unanimous about them. Four of them concern males, and only one a woman. The twenty confirmed burnings were divided between the Westfjords (8), the North (4), and the Southwest (8 in the Parliamentary Plains = Tingvellir).

Books of magic

Probably quite a few existed, but only seven are clearly documented. It is difficult to decide the background of the magic characters. Some may be traced to the mysticism of the Middle Ages and the renascence teachings, but others suggest pagan and runic culture. The witchcraft mentioned at trials in the 17th century, can in many instances be found in the books of magic still preserved in manuscript museums. The purpose of the magic characters reveals in many instances the worries, toil, and the labour of the public.

Herbs

Various herbs still play a role in popular belief and are considered to be helpful, especially healing. During earlier centuries the boundaries between scorcery, superstition and dogma on one side, and modern medicine and natural sciences on the other, were vague. Primitive remedies, interpretation of various natural phenomena, and belief in healing qualities of herbs and stones, were the main reasons for executions.

Magical and natural stones were used for many purposes. Belief in them is ancient. They are even mentioned in the oldest codes of the country, where it is strictly forbidden to use them or magnify their potential. In the Middle Ages, the boundaries between witchcraft, superstition, and dogma on one side, and medicine and modern natural science were unclear. Nowadays many herbs and stones are used for healing purposes.

Tales of witchcraft and scorcery can be found in many books on mythology and folklore.

Confirmed burnings in Iceland in the 17th century in cronological order:

Abbreviations below: N = North Iceland; SW = Southwest Iceland; W = Westfjords.

N. Jon Rognvaldsson 1625. Farmer Sigurdur at Urdir in valley Svarfadardalur suffered much from a ghost. Jon Eyfirdingur was accused for its existence and sending it to Sigurdur to kill him and/or cause him harm. It only managed to kill a few horses. Magistrage Magnus Björnsson got the case. He interrogated Jon, who denied the accusations flatly. His house was searched and a few suspicious runic letters were found. This discovery was considered sufficient to sentence him to the stake at Meleyrar in valley Svarfadardalur. His case was never confirmed by the official court of the Parliamentary. The next burning probably occurred nine years later, but the sources are too vague.

W. Tordur Gudbrandsson 1654. Sickness and hard times struck the people on cove Trekyllisvik in 1652, especially the women, who started getting sick after the referrendum in 1651. Then the magistrate, Torleifur Kortsson, agreed to the demand of the mother and brothers of Gudrun Hrobjartsdottir, that she should leave the domestic service of farmer Tordur Gudbrandsson. She was taken dangerously ill, when her brothers came for her, but she recovered immediately after the departure. Again she fell ill after leaving the church there, but was again quite well upon arrival at farm Munadarnes. Tordur was accused for her sickness. He admitted that the devil had appeared to him as an archtic fox and that he had used exorcism to get his help. Tordur was burned at the stake at Kista on cove Trekyllisvik.

W. Egill Bjarnason 1654. When Tordur’s case was investigated, suspicion of more widespread use of witchcaraft in the area arose. Egill Bjarnason became the centre of attention and he was emprisoned. He confessed to scorcery and connections to the devil, who was contracted to him. He went his errands to cause harm and havoc, killed sheep at the farms Hlidarhus and Kjorvogur. Egill was sentenced to burn at the stake with Tordur at Kista.

W. Grimur Jonsson 1654. Just before Tordur was burned, he said that Grimur was the greatest scorcerer of Trekyllisvik. These words lead to an investigation, whch supported his reputation as a sorcerer. He confessed to using runic boards from Tordur as defence against attacks of foxes on his sheep herds. He promised to amend his ways, if he were released from his shackles. When he was not released, he confessed to all kinds of scorcery, and was burned at Kista as well, Kista is also name fore Trekyllisvik.

W. Jon Jonsson senior 1656. A father and a son from farm Kirkjubol, both by the name Jon, were accused of scorcery, causing sickness and anguish to reverend Jon Magnusson at parsonage Eyri on the bay Skutulsfjordur. They confessed after several months’ emprisonment. Jon senior confessed to owning two books on witchcraft, having destroyed two milking cows, and assisted his son in causing the reverend harm. They were both sentenced and burned at farm Kirkjubol on bay Skutulsfjordur.

W. Jon Jonsson junior 1656 confessed to more scorcery than his father before they were burned. He told about unsuccessful healing attempts and having experienced the devil in his sleep. He confessed extraordinary efforts to gain the love of the reverend’s daughter.

SW. Torarinn Halldorsson 1667 lived at farm Birnustadir and practised medicine on people and animals in county Ogursveit. He used a runic oak board in his efforts to cure an young girl at farm Laugabol. She died and reverend Sigurdur Jonsson at Ogur obtained the runic board. An inspection at the spring parliament was inconclusive. A short time later, the reverend died, and that was considered enough evidence against Torarinn for both deaths. He fled, shaved his hair and beard, but was recognised and seized in county Stadarsveit on the peninsula Snaefellsnes, and sent back in shackles. He escaped again and was sent back from district Rangarvellir. His trial was both positive and negative for him. During the session of the spring parliament in 1667, no-one volunteered an oath for him, and he was sentenced and sent to the Parliamentary Plains, where the court decided to burn him at the stake. He was probably the first to be executed that way in the southwest part of the country.

SW. Jon Leifsson 1669. Mrs. Helga Halldorsdottir at farm Selardalur on the bay Arnarfjordur fell ill at the turn of the year 1968 and felt great anguish caused by evil spirits well into the next summer. The devilry continued in the whole valley after she fell ill and everyone left for a while. Mr. Jon Leifsson had wanted to marry one of the female servants of farm Selardalur, but Mrs. Helga opposed the proposal. She blamed Jon for her illness. Interrogations revealed his participation in scorcery, and for a while the authorities were undecided about the procedings. The magistrate Eggert solved the problem alone and decided to burn him at the stake in the valley just before the assembly of the common parliament. The court of the parliament confirmed his decision afterwards.

N. Erlendur Eyjolfsson 1669. Jon Leifsson alleged shortly before his execution, that Erlendur had tought him witchcraft. Therefore dean Pall sent governor Torleifur Kortsson a letter, accusing Jon for allt the misgivings of his family in valley Selardalur, and also Erlendur for being an accessory. This was sufficient evidence for the authorities, and Erlendur was burned at the stake in county Vesturhop in district Hunavatnssysla the same year. He confessed to scorcery and teaching it as well.

SW. Sigurdur Jonsso 1671 was born in county Ogurhreppur and was accused of the sickness of a housewife on the bay Isafjardardjup. He confessed to scorcery, using all kinds of herbs, feather pens, magic poetry, and runic oak boards. He claimed to have defended himself against the devil and ghosts by scorcery. He was seized on the island Vigur and was burned at the stake in the Parliamentary Plains in the summer.

SW. Pall Oddsson 1674 was born at farm Anastadakot on the peninsula Vatnsnes, where he lived for decades before he was accused of scorcery. Reverend Torvardur Olafsson at parsonage Breidabolstadur blamed him for his wife’s sickness, because of runic boards, which were discovered. Pall could not make it to the parliament, where his case was debated. His absence was to his disadvantage. Governor Torleifur Kortsson continued the case and kept Pall emprisoned in the hands of magistrate Gudbrandur Arngrimsson at his farm As in valley Vatnsdalur. The magistrate is said to have influenced the quick procedings against Pall, because of his affair with the magistrate’s wife. More accusations against Pall appeared, and the case was referred to the parliamentary court, where Pall had the opporunity to defend himself with the oath of twelve persons. Five of them changed their minds about the oath, but Pall never confessed. One man swore to having seen him write runes on an oak board. He was sentenced to burn at the stake at the Parliamentary Plains.

SW. Bodvar Torsteinsson 1674 was commonly known as a scorcerer. He was born on the peninsula Snaefellsnes and was burned on the same day as Pall Oddson. He twaddled about his scorcery in a fishing station at Gufuskalar. He was asked if he had caused the failed catch of Dean Bjorn Snaebjornsson’s boat, and he confessed. Dean Bjorn pressed charges. Bodvar withdrew his confession in vain and was burned at the stake in the Parliamentary Plains.

N. Magnus Bjarnason 1675. The witch hunt was relentless in valley Selardalur in spite of the burning of two people. The housewife fell ill again and two of her sons as well. Now the family blamed Magnus Bjarnason on the bay Arnarfjordur. One magic letter was discovered and governor Torleifur Kortsson claimed a confession. He had Magnus transported to Thingeyrar in district Hunavatnssysla, where he was burned.

SW. Lassi Didriksson 1675 was, at the age of seventy, blamed for the sickness of reverend Pall’s wife and sons in valley Selardalur. The illness of Egill Helgason, one of magistrate Eggert’s men, was added. The magistrate was the reverend’s brother. Lassi denied vehemently being a scorcerer. Governor Torleifur Kortsson found no proof and referred the case to the Parliament Court. There Lassi was sentenced to burn at the stake. Heavy rain made the burning extremely difficult and put out the fire thrice. Magistrate Eggert broke a leg on his way back home, which was construed by many as proof of Lassi’s innocence.

SW. Bjarni Bjarnason 1677. His roots were in valley Breiddalur on bay Onundarfjordur. Bjani Jonsson’s wife at farm Hafurshestur on bay Onundarfjordur deemed him responsible for her seven years illness. After Bjarni was charged, the wife got sicker and died before he was sentenced. He admitted to owning magic letters and no-one was willing to swear an oath in his favour. His prosecutor was the governor, Torleifur Kortsson, who got the verdict guilty. Bjarni was burned at the stake on July 4th.

SW. Torbjorn Sveinsson 1677. His ancestry was traced to district Myrarsysla. He carried three booklets on scorcery and other items on his person. He admitted to experimenting with scorcery, i.e. to calm his herd of sheep. Nothing is documented about him harming others. He had been branded and whipped for theft. He and Bjarni were burned together in the Parliamentary Plains.

N. Stefan Grimsson 1678. His ancestors also lived in the Borgarfjordur area. He was blamed for distroying eight cows and admitted to all kinds of delinquencies after he had been sentenced, but he never confessed to scorcery. The connection of his case to reverend Arni Jonsson’s case were a part of the reason. The reverend managed to leave the country before a convocation had been gathered to handle his case. Torbjorn was burned at the stake in district Hunavatnssysla immediately after the sentence.

W. Turidur Olafsdottir & Jon Helgason 1678. Documented sources about the burning of the woman, Turidur, and her son are vague. They most probably were accused by reverend Pall in valley Selardalur of his wife’s sickness. They arrived from district Skagafjordur in the summer of 1677 and were strangers in their new surroundings. According to chronicles, Jon, the son, told people, that they had travelled on foot and forded rivers without horses or ferries, which was a sign of his mother’s witchcraft. They were both burned at the stake in district Bardastrandarsysla.

SW. Ari Palsson 1681. Torkatla Snaebjornsdottir, the sister of Bjorn at parsonage Stadarstadur, who played his role in the burning of Bodvar Torsteinsson a few years earlier, was the instigator of Ari’s case. She accused him on the grounds of a runic board, which he left behind at her home. This evidence was devastating, because many people believed, that he was guilty of making many people ill. After the sentence, he confessed to scorcery. Arni Magnusson and Pall Vidalin sent a report to the government in Copenhagen on the justice system in Iceland, and mentioned this case as an example of a judicial murder. Ari was burned at the stake in the Parliamentary Plains.

W. Sveinn Arnason 1683. His accuser was dean Sigurdur Jonsson, who wrote about this case in his chronicles. He claimed that Sveinn had caused his wife’s illness. She was the daughter of Pall in valley Selardalur. His prosecutor was Magnus Jonsson. He was convicted on the spit of land called Nauteyri and burned in the forest Arngerdareyrarskogur. According to popular belief, he was to be transported to the Parliamentary Plains for his execution, but those who were responsible for him did not bother.

Sources: Ólína Þorvarðardóttir, Dr.Phil –

Translation in English by nat.is

Main Photo Credit: Rila monastery, Bulgaria

According to the Book of Settlements and the Sturlunga Saga,

many murders, executions and slayings took place in Iceland.

Hunted Pleases in Iceland

Witchcraft and sorcery in Icelandic

Get an education when travel: