Icelandic Literature

The Icelandic Literature was created by the inhabitants of Iceland from the country’s settlement in the 9th century AD to the present. Because Old Norse and Icelandic are, for all practical purposes, the same language, Icelandic medieval writings are sometimes referred to as Old Norse literature.

The Sagas

Iceland is most famous for its medieval sagas, written between the 12th and 14th centuries. Sagas are tales of Norwegian kings and real or legendary heroes, both men and women, of Iceland and Scandinavia. Composed in prose, generally by unknown authors, they are thought to have been widely recited by storytellers before being committed to writing. None of the original manuscripts is extant; transcripts and collections, sometimes with revisions and amplifications of the originals, date from the 13th century and after.

Hundreds of sagas were written in medieval Iceland. They may be divided into kings’ sagas, such as Snorri Sturluson’s Heimskringla, which traces the rulers of Norway from legendary times to 1177, and Knytlinga Saga, dealing with Danish kings from Gorm the Old to Canute IV; legendary sagas, which are basically knightly romances and fantasies (sometimes called “lying” sagas) of varying literary merit; and the sagas of Icelanders—more or less fictionalized accounts of the so-called Saga Age (900-1050) in Iceland. To the last category belong such highly accomplished literary works as Egil’s Saga, the life of the warrior-poet Egill Skallagimsson; Laxdaela Saga, a triangular love story; Gisla Saga, the tragic tale of a heroic outlaw; and Njal’s Saga, generally considered the high point of Icelandic literary art, a complex and rich account of human and societal conflicts.

In addition, the saga form was used in the 13th century to write contemporary history as it evolved around pre-eminent personages of the time. The result is generally known under the collective name of Sturlunga Saga; it recounts in gory detail the internecine struggle of the 13th century that led to the end of the old Icelandic commonwealth. The best of its components is the Islendinga Saga of Sturla Thordarson, a nephew of Snorri Sturluson. Other historical writings of medieval Iceland include the Islendingabok (Book of Icelanders) by Ari Thorgilsson the Learned and the Landnamabok (Book of Settlements), in which Ari may also have had a hand.

The Eddas and Other Poetry

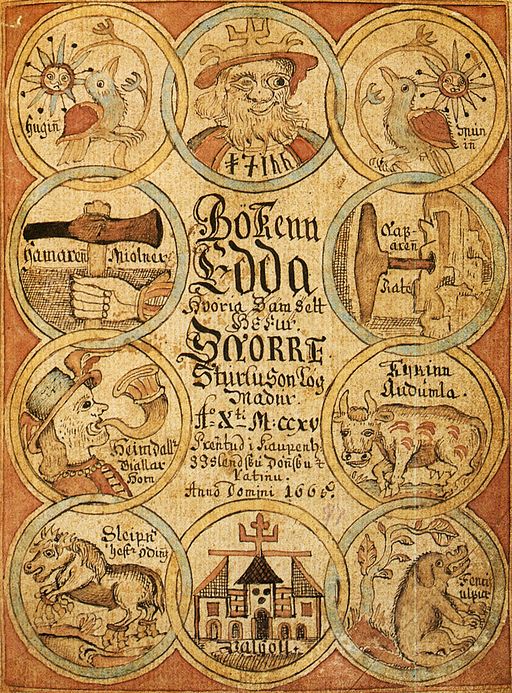

Early Icelandic literature also included the so-called Eddas and skaldic poetry. The term Edda is of doubtful origin. It may be derived from the Old Norse word edda (great-grandmother), but more likely refers to Oddi, a seat of culture in southern Iceland. (Oddi was the residence, at different times, of Saemundur Sigfusson, a learned cleric once thought to have compiled one of the Eddas, and Snorri Sturluson, who is known to have written the other. It is also possible that the term refers to the Old Norse word othr (“poetry”). In any case, the term is used for two famous collections of Icelandic literature. The Poetic Edda, Elder Edda (9th-12th century), is a group of more than 30 poems on the Scandinavian and Germanic gods and on human heroes, notably Sigurdur, the Icelandic counterpart of the German Siegfried (Nibelungenlied). Some of these poems may possibly have been composed outside Iceland, but they were apparently first written down there in the 12th century.

The Prose Edda, or Younger Edda (13th century), is the work of Snorri Sturluson. It includes tales from Scandinavian mythology and is the most important source of modern knowledge on this subject. Other sections of the Prose Edda form a guide to poetic diction and a metrical key.

Skaldic poetry, composed between the 9th and 13th centuries, was written variously in honour of the nobles, in praise of love, or to satirize or commemorate current happenings. Not as free as Eddic verse, it is strictly syllabic in structure and is characterized by the use of kennings: complex periphrases that at their best are beautiful metaphors, but also sometimes give skaldic poetry the effect of riddles.

Period of Literary Sterility

After Iceland’s loss of independence in the 1260s, Icelandic literature declined, and from about 1400 to the 19th century hardly any literary prose was written, with the exception of a notable Icelandic translation of the Bible by 16th-century Protestant theologians. Sacred verse, however, was composed, and so were rimur, an Icelandic form of balladry more remarkable for metrical ingenuity than literary value, which continued to be popular until the end of the 19th century. The outstanding work of these centuries—and the one that is more often printed than any other in Iceland—is the Passiusalmar (1666, Hymns of the Passion) by Hallgrimur Petursson, a 17th-century Lutheran pastor.

Modern Icelandic Literature

With the 19th century, a linguistic revival and a resurgence of literary creativity began in Iceland. Throughout the century, the influence of European literary movements was felt. Romanticism, dominant in the 1830s and characteristic of the work of such poets as Bjarni Thorarensen and Jonas Hallgrimsson, was succeeded by Realism and Naturalism in prose fiction. The modern Icelandic novel may be said to have begun with Lad and Lass (1850; trans. 1890), a description of contemporary life by Jon Thoroddsen, a poet as well as a novelist. This early Icelandic fiction either is introspective in mood, as in the first novels of Einar Kvaran, or is given to clearly detailed pictures of stark rural life—as in Heidarbylid (1908-1911, The Mountain Farm), a four-volume cycle by Gudmundur Magnusson, who wrote under the pen name Jon Trausti.

Realism, in the form of satire, is manifested in the short stories of Gestur Palsson and, in the ironic vein, in the poetry of Stephan G. Stephansson. An expatriate who lived as a farmer in Canada, Stephansson was noted for his sensitive use of language. Another major poet who lived abroad for extended periods of time was Einar Benediktsson, a writer in the lyrical vein who instilled his work with a pantheistic vision.

Outstanding prose writers in the 20th century have included Gunnar Gunnarsson, a master of characterization who wrote many of his novels in Danish, and Thorbergur Thordarson, a superb stylist who won a wide following with his humorous autobiographical writings. The Icelandic author best known outside Iceland is Halldor Laxness, who was awarded the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1955. Among his Expressionist, epic novels of Icelandic life are Salka Valka (1931-1932; trans. 1936), Independent People (1934-1935; trans. 1945), and World Light (1937-1940; trans. 1969). Post-World War II works include a novel about a would-be singer, The Fish Can Sing (1957; trans. 1966) and Innansveitarkronika (1970, A Parish Chronicle). Among the several significant novelists now writing are Olafur Johann Sigurdsson, author of such masterly novellas as The Changing Earth (1947; trans. 1979) and Bref sera Bodvars (1965, Pastor Bodvar’s Letter); Indridi G. Thorsteinsson, who has recorded the stresses in 20th-century Icelandic society in novels such as North of War (1971; trans. 1981); Gudbergur Bergsson, an ironic commentator on the foibles of ordinary people; and Svava Jakobsdottir, author of the symbolic Leigjandinn (1969, The Lodger).

The Neo-Romantic David Stefansson, who sought inspiration in folklore and ballads, and Tomas Gudmundsson, already a classic master of style and diction, who became the city poet of Reykjavík, represent traditional poetry in the 20th century. Newer trends were championed by Steinn Steinarr, whose modernist expression was synthesized in Timinn og vatnid (1948, Time and the Water). The most accomplished of contemporary poets tend to merge the traditional with a modern approach. Among them are Sigurdsson and Snorri Hjartarson, both of whom have won the Nordic Council’s literary prize, Hannes Petursson, and Matthias Johannessen.

Drama, a form not significant in Icelandic literature until the turn of the 20th century, is today represented by the work of such writers as Agnar Thordarson, whose Atoms and Madams (1957; trans. 1967) is a satire of modern city life, and Jokull Jakobsson, brother of Svava Jakobsdottir, who wrote brittle, evocative plays in a Chekhovian vein.

Iceland has an exceptionally high rate of literacy — more books are produced per capita than in most other countries in the world.

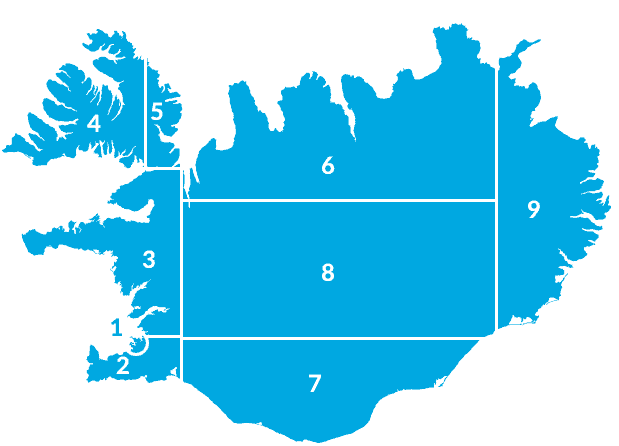

Icelandic Saga:

Saga trail South

Saga trail East

Saga trail North

Saga trail Strandir

Saga trail Westfjords

Saga trail West

Saga trail Reykjavik area

Saga trail Reykjanes

Saga trail Highland

Troll lives in Iceland

nat.is Travel guide for complete Iceland